倾听非洲:BAABA MAAL

Baaba Maal(巴巴.马尔), 非洲新一代音乐家的杰出人物。用现代技术重新演绎非洲传统节奏和民歌。

他出生于塞内加尔北部地区,用PULAAR语(Fula族,游牧民族)演唱。他的高音清澈动人,被称为“塞内加尔的夜莺”。他小时侯学习科拉琴(一种西非弦乐器,形似竖琴),而后改习吉他。他曾在达喀尔(塞内加尔首都)的音乐学校学习,他曾用一年多时间沿着塞内加尔河游历,从一个村庄到另一个村庄,向老艺人学习。1982年他获得奖学金前往巴黎的Ecole des Beaux Arts学习作曲和编曲。在巴黎期间,他遇到了盲人歌手Mansour Seck,学成后他们回国创建了Dande Lenol(or "Voice of the People",人民之声)乐队,并成为非洲流行音乐界混合hip-hop, reggae 和 techno等音乐元素的重要角色。其重要专辑《Firin' in Fouta》(1994)为乐队带来了巨大的成功。MAAL还是当地民间音乐团体的成员,只用非洲传统乐器演奏。

MAAL推崇乡村生活,积极参与非洲妇女权利运动;他歌唱历史和英雄,把过去的经验和教训带给今天的非洲。他在音乐里讨论的主题是妇女角色的改变,非洲人的自信心,部落冲突的解决等现实问题。

MAAL的专辑列表:

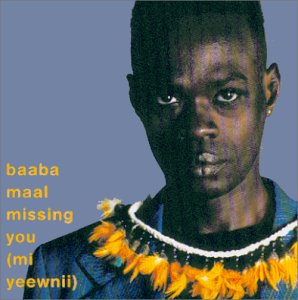

1 Mi Yeewnii(MISSING YOU),Released Jun 5 2001

2 Jombaajo,Original Release Date: May 2, 2000

3 Taara,Released Nov 24 1997

4 Baayo,Released May 21 1991

5 Djam Leelii: The Adventurers [Yoff],Released Nov 3 1998

6 Wango,Released Mar 8 1994

7 Nomad Soul,Released Jul 14 1998

8 Live at the Royal Festival Hall [CD],Released Mar 16 1999

9 Souka Nayo (I Will Follow You) [US],Released Nov 3 1998

下面是BOB DORAN做的访谈录,太长了没有翻译,有兴趣的自己看吧。

Q: Could you tell me about growing up in Podor?

Baaba: Podor is a nice town. It's at the north of Senegal near the river. The town faces the other country that is Mauritania. It is a very cultural town, because at the beginning it was closest stop when you come from the Sahara and also when you come from the south to go to the north part of Africa. It was just at the middle, and so it's where a lot of cultures of West Africa come together.

Q: What did your family do there? What did your father do?

Baaba: My father was a muezzin at the mosque. He was singing and calling people to come to pray. He was very involved in the religion.

Q: So his involvement in music was mostly through religion?

Baaba: Yes, it's like when you talk about gospel in America. People used to make music when there was a religion party, a ceremony in the night and they would be singing the whole night.

Q: Did your mother sing too?

Baaba: She sang when she was very young. We had some kinds of popular music that everyone can do, especially the young people when they'd finish their work at the fields. They'd meet and would sing all night talking about the life of young people, about their hopes, about what they learn in their families.

Q: Did your parents teach you music?

Baaba: I learned some from my mother who taught me the songs. With my father, I'd just stay near him and listen and try to find how he did his music.

Q: On your album in the song Salimoun, you speak of the wisdom of the mothers. What did you learn from your mother?

Baaba: I think that I learned music. And also you learn recommendations that you can use in your life. When you travel, you all the time remember what your mother teach you. You know in the African family the mother has a big role to play because the father is outside in the fields or going to work. And the mother is all the time in the house making food for the children or for the whole family and educating the children. That's why a lot of things that you use in the world, you learn from your mother, more from your mother than from your father.

Q: You became a musician even though in the traditional caste system that is a role for those born as griots. I wonder is the system breaking down?

Baaba: Yeah, the system is going little by little because a lot of things are changing in Africa now. And the money brings it because in the beginning the griots would play just for the families of the kings. When the people have a big ceremony they'd come and play for everyone, but it was mostly for just one family. Every family of griots has some family that they follow in life and they sing about the relationship between them and the other family. Now this thing is finished because of the things changing in Africa. When I started singing it was a big problem because the (old system) was not totally finished and they could not understand how someone who is a not a Griot could go and sing. It was the young generation who accepted me because they go like me to their school and they understand that if you have the opportunity to be a singer or do another work, even though you don't belong to the caste you can do it, because the whole world is going like that.

Q: Tell me about how you put together your album, Fire In Fouta. I heard that you returned to Podor to record some village music.

Baaba: I worked with a producer on some songs that we were planning to put in the album. After that I went to the north and organized a big party, a party where all the people who lived in the town, who were not professional musicians but they use the music for everything in their life. We invited them and they played all the different kinds of music that we have there. They play also in the music we were putting in the album, and they do it so naturally because all this kind of new beat that people say is modern, we have a reference of that kind of music in our traditional music. We have something that looks like it, like the rap music, we have something in traditional Senegalese music called tasso that is close to rap music.

Q: In the first song Sidiki , in the middle of the song there is a rhythm that sounds like pounding. What is that?

Baaba: It's the women in the north of Senegal at Podor who sometimes when they make the food with their millet pounding, they do it with music. At every moment of their life, these people use the music to do their work. We used samples of that in the album.

Q: What are your plans for the future?

Baaba: Right now I'm still working on promotion for my album. So I am making a tour. We are planning to make some tapes for Africa in traditional music and also to make an African tour, because for a long time we haven't done that. We tour in Europe and America and the rest of the world but not in Africa.

Q: So you will record material just for Africa?

Baaba: Yes, sometimes, yes.

Q: How do you feel about your music being categorized here as "world music"?

Baaba: I don't care. I did not like that name "world music" in the beginning. I think that African music must get more respect than to be put in a ghetto like that. We have something to give to others. When you look to how African music is built, when you understand this kind of music, you can understand that a lot of all this modern music that you are hearing in the world has similarities to African music. It's like the origin of a lot of kinds of music.

Q: It's the basis of jazz...

Baaba: Yes, jazz and blues and rap music itself. As I said the tasso is the real rap music.

Q: What is the Yela rhythm?

Baaba: All kinds of music comes from the big empires like of the empire of Ghana, it was before the empire of Mali. At the beginning the people were using calabashes to make the rhythm. Women were singing the songs and sometimes men brought the music from them and told about the history of the village or the history of the society. Little by little we put in the African traditional guitar and after that we put the western guitar. In the 1960s years we put the western guitar and the music changed from its original way to something that was more popular, that everyone can use.

Q: Is there a connection between Yela and Reggae?

Baaba: Yeah, they look close to the same because the way the Reggae music is arranged, the traditional African music that we call Yela is like that. The construction of the music itself looks close to the same. When you put a Reggae song in the villages, the women who used to dance the Yela, they still dance it like Yela because they feel that it is the same.

Q: Your friend and collaborator, the Griot Mansour Seck, is he of the same family as (the other popular Senegalese musicians,) Thione Seck and Coumba Gawlo Seck?

Baaba: It's the same name and the origins must be the same, but it's not the same family because it's not the same language they are talking. Mansour is Fula the others are Wolof. But people say that all the griots come from the same family.

Q: And Mansour is your family's Griot?

Baaba: Yes, his father was a friend to my father.

Q: Do you see your role as sort of the "new Griot"?

Baaba: Yes, it is true, because we are at the center of African society like the old griots who were at the center of the old society. The people live with our music, they listen more to what we are saying than to what politicians are saying. This is the role that the older griots were playing in the African kingdoms at the beginning. And now this is our role.

Q: The song Nilou talks about the devaluation of the African franc but also about the Western intervention in African affairs.

Baaba: Yes, when something happens in my society I have to talk about it. Because every different tribe finds their solution, so I try let people understand what's happening and there is a solution when they face that problem. We also understand that it is not new in Africa, this intervention, especially in Senegal. It's not new that the French have to decide at every moment of our lives what's going to be the future of our continent in a lot of things, in the economical things and the political things. But as musicians we understand that now we must face that and know that the future of Africa must belong only to the people who live in Africa. They must work for that. Especially after this year where many people on this continent who have nothing, who are very poor and have nothing to bring to the world, every time they are holding out their hands asking for something from the others. There is a new generation of musicians, of people like me who are ready to bring their ideas. They know they are African, they know that is their personality, but also they know that they can bring something to the world, something that belongs to them.

Q: What is it you want to bring to the world? What message do you have for the world?

Baaba: The way of living that is very African, I think the people lose it in the world. When you come to an African concert you see people on the stage with clothes with a lot of color, dancing, singing, smiling. This is the real self of Africa. With all our problems people are still living together. It's true we have some examples that are not very good, like Rwanda, but in villages like in Senegal, and other parts of Africa, people are living together, getting together, working and helping each other and have a very good harmony between them. The notion of family is still there. Respect that you must give to your father and your mother or someone who is older than you. All these things we are getting from the music and we see that the rest of the world is losing the importance of the human being. It's still there in most countries in Africa.

Q: So that is part of what you say with your music?

Baaba: We talk about all the problems in the world like racism. Sometimes the problems between people come because people don't try to know the other. They don't try to understand the other. In Africa we don't have that. When you live in one village you go out in the street, and you have to look after everyone. When someone needs food and you have it, you have to eat it with him. It's very important because one day you will want something like that.

Q: In your new music you are combining the traditional with the modern. Do you see that as a danger to the traditional music?

Baaba: It's not a danger because in the world now we know that we have something that is very important, traditional African music that is talking just to the African society because they understand it. They live with it, they grow up with this kind of music. But now when you play music you play not just for only your own society, you play for the whole world. The world is one planet, it's like one big village. You must show what you learn from your house and combine it with what is your experience in life. People travel, they go off to school and know what's happening in the other part of the world, they look at the television, they read the newspaper, and everyone is very involved in what's happening on the other side of the world. You must be an African talking to the rest of the world, or an American talking to the rest of the world.

他出生于塞内加尔北部地区,用PULAAR语(Fula族,游牧民族)演唱。他的高音清澈动人,被称为“塞内加尔的夜莺”。他小时侯学习科拉琴(一种西非弦乐器,形似竖琴),而后改习吉他。他曾在达喀尔(塞内加尔首都)的音乐学校学习,他曾用一年多时间沿着塞内加尔河游历,从一个村庄到另一个村庄,向老艺人学习。1982年他获得奖学金前往巴黎的Ecole des Beaux Arts学习作曲和编曲。在巴黎期间,他遇到了盲人歌手Mansour Seck,学成后他们回国创建了Dande Lenol(or "Voice of the People",人民之声)乐队,并成为非洲流行音乐界混合hip-hop, reggae 和 techno等音乐元素的重要角色。其重要专辑《Firin' in Fouta》(1994)为乐队带来了巨大的成功。MAAL还是当地民间音乐团体的成员,只用非洲传统乐器演奏。

MAAL推崇乡村生活,积极参与非洲妇女权利运动;他歌唱历史和英雄,把过去的经验和教训带给今天的非洲。他在音乐里讨论的主题是妇女角色的改变,非洲人的自信心,部落冲突的解决等现实问题。

MAAL的专辑列表:

1 Mi Yeewnii(MISSING YOU),Released Jun 5 2001

2 Jombaajo,Original Release Date: May 2, 2000

3 Taara,Released Nov 24 1997

4 Baayo,Released May 21 1991

5 Djam Leelii: The Adventurers [Yoff],Released Nov 3 1998

6 Wango,Released Mar 8 1994

7 Nomad Soul,Released Jul 14 1998

8 Live at the Royal Festival Hall [CD],Released Mar 16 1999

9 Souka Nayo (I Will Follow You) [US],Released Nov 3 1998

下面是BOB DORAN做的访谈录,太长了没有翻译,有兴趣的自己看吧。

Q: Could you tell me about growing up in Podor?

Baaba: Podor is a nice town. It's at the north of Senegal near the river. The town faces the other country that is Mauritania. It is a very cultural town, because at the beginning it was closest stop when you come from the Sahara and also when you come from the south to go to the north part of Africa. It was just at the middle, and so it's where a lot of cultures of West Africa come together.

Q: What did your family do there? What did your father do?

Baaba: My father was a muezzin at the mosque. He was singing and calling people to come to pray. He was very involved in the religion.

Q: So his involvement in music was mostly through religion?

Baaba: Yes, it's like when you talk about gospel in America. People used to make music when there was a religion party, a ceremony in the night and they would be singing the whole night.

Q: Did your mother sing too?

Baaba: She sang when she was very young. We had some kinds of popular music that everyone can do, especially the young people when they'd finish their work at the fields. They'd meet and would sing all night talking about the life of young people, about their hopes, about what they learn in their families.

Q: Did your parents teach you music?

Baaba: I learned some from my mother who taught me the songs. With my father, I'd just stay near him and listen and try to find how he did his music.

Q: On your album in the song Salimoun, you speak of the wisdom of the mothers. What did you learn from your mother?

Baaba: I think that I learned music. And also you learn recommendations that you can use in your life. When you travel, you all the time remember what your mother teach you. You know in the African family the mother has a big role to play because the father is outside in the fields or going to work. And the mother is all the time in the house making food for the children or for the whole family and educating the children. That's why a lot of things that you use in the world, you learn from your mother, more from your mother than from your father.

Q: You became a musician even though in the traditional caste system that is a role for those born as griots. I wonder is the system breaking down?

Baaba: Yeah, the system is going little by little because a lot of things are changing in Africa now. And the money brings it because in the beginning the griots would play just for the families of the kings. When the people have a big ceremony they'd come and play for everyone, but it was mostly for just one family. Every family of griots has some family that they follow in life and they sing about the relationship between them and the other family. Now this thing is finished because of the things changing in Africa. When I started singing it was a big problem because the (old system) was not totally finished and they could not understand how someone who is a not a Griot could go and sing. It was the young generation who accepted me because they go like me to their school and they understand that if you have the opportunity to be a singer or do another work, even though you don't belong to the caste you can do it, because the whole world is going like that.

Q: Tell me about how you put together your album, Fire In Fouta. I heard that you returned to Podor to record some village music.

Baaba: I worked with a producer on some songs that we were planning to put in the album. After that I went to the north and organized a big party, a party where all the people who lived in the town, who were not professional musicians but they use the music for everything in their life. We invited them and they played all the different kinds of music that we have there. They play also in the music we were putting in the album, and they do it so naturally because all this kind of new beat that people say is modern, we have a reference of that kind of music in our traditional music. We have something that looks like it, like the rap music, we have something in traditional Senegalese music called tasso that is close to rap music.

Q: In the first song Sidiki , in the middle of the song there is a rhythm that sounds like pounding. What is that?

Baaba: It's the women in the north of Senegal at Podor who sometimes when they make the food with their millet pounding, they do it with music. At every moment of their life, these people use the music to do their work. We used samples of that in the album.

Q: What are your plans for the future?

Baaba: Right now I'm still working on promotion for my album. So I am making a tour. We are planning to make some tapes for Africa in traditional music and also to make an African tour, because for a long time we haven't done that. We tour in Europe and America and the rest of the world but not in Africa.

Q: So you will record material just for Africa?

Baaba: Yes, sometimes, yes.

Q: How do you feel about your music being categorized here as "world music"?

Baaba: I don't care. I did not like that name "world music" in the beginning. I think that African music must get more respect than to be put in a ghetto like that. We have something to give to others. When you look to how African music is built, when you understand this kind of music, you can understand that a lot of all this modern music that you are hearing in the world has similarities to African music. It's like the origin of a lot of kinds of music.

Q: It's the basis of jazz...

Baaba: Yes, jazz and blues and rap music itself. As I said the tasso is the real rap music.

Q: What is the Yela rhythm?

Baaba: All kinds of music comes from the big empires like of the empire of Ghana, it was before the empire of Mali. At the beginning the people were using calabashes to make the rhythm. Women were singing the songs and sometimes men brought the music from them and told about the history of the village or the history of the society. Little by little we put in the African traditional guitar and after that we put the western guitar. In the 1960s years we put the western guitar and the music changed from its original way to something that was more popular, that everyone can use.

Q: Is there a connection between Yela and Reggae?

Baaba: Yeah, they look close to the same because the way the Reggae music is arranged, the traditional African music that we call Yela is like that. The construction of the music itself looks close to the same. When you put a Reggae song in the villages, the women who used to dance the Yela, they still dance it like Yela because they feel that it is the same.

Q: Your friend and collaborator, the Griot Mansour Seck, is he of the same family as (the other popular Senegalese musicians,) Thione Seck and Coumba Gawlo Seck?

Baaba: It's the same name and the origins must be the same, but it's not the same family because it's not the same language they are talking. Mansour is Fula the others are Wolof. But people say that all the griots come from the same family.

Q: And Mansour is your family's Griot?

Baaba: Yes, his father was a friend to my father.

Q: Do you see your role as sort of the "new Griot"?

Baaba: Yes, it is true, because we are at the center of African society like the old griots who were at the center of the old society. The people live with our music, they listen more to what we are saying than to what politicians are saying. This is the role that the older griots were playing in the African kingdoms at the beginning. And now this is our role.

Q: The song Nilou talks about the devaluation of the African franc but also about the Western intervention in African affairs.

Baaba: Yes, when something happens in my society I have to talk about it. Because every different tribe finds their solution, so I try let people understand what's happening and there is a solution when they face that problem. We also understand that it is not new in Africa, this intervention, especially in Senegal. It's not new that the French have to decide at every moment of our lives what's going to be the future of our continent in a lot of things, in the economical things and the political things. But as musicians we understand that now we must face that and know that the future of Africa must belong only to the people who live in Africa. They must work for that. Especially after this year where many people on this continent who have nothing, who are very poor and have nothing to bring to the world, every time they are holding out their hands asking for something from the others. There is a new generation of musicians, of people like me who are ready to bring their ideas. They know they are African, they know that is their personality, but also they know that they can bring something to the world, something that belongs to them.

Q: What is it you want to bring to the world? What message do you have for the world?

Baaba: The way of living that is very African, I think the people lose it in the world. When you come to an African concert you see people on the stage with clothes with a lot of color, dancing, singing, smiling. This is the real self of Africa. With all our problems people are still living together. It's true we have some examples that are not very good, like Rwanda, but in villages like in Senegal, and other parts of Africa, people are living together, getting together, working and helping each other and have a very good harmony between them. The notion of family is still there. Respect that you must give to your father and your mother or someone who is older than you. All these things we are getting from the music and we see that the rest of the world is losing the importance of the human being. It's still there in most countries in Africa.

Q: So that is part of what you say with your music?

Baaba: We talk about all the problems in the world like racism. Sometimes the problems between people come because people don't try to know the other. They don't try to understand the other. In Africa we don't have that. When you live in one village you go out in the street, and you have to look after everyone. When someone needs food and you have it, you have to eat it with him. It's very important because one day you will want something like that.

Q: In your new music you are combining the traditional with the modern. Do you see that as a danger to the traditional music?

Baaba: It's not a danger because in the world now we know that we have something that is very important, traditional African music that is talking just to the African society because they understand it. They live with it, they grow up with this kind of music. But now when you play music you play not just for only your own society, you play for the whole world. The world is one planet, it's like one big village. You must show what you learn from your house and combine it with what is your experience in life. People travel, they go off to school and know what's happening in the other part of the world, they look at the television, they read the newspaper, and everyone is very involved in what's happening on the other side of the world. You must be an African talking to the rest of the world, or an American talking to the rest of the world.

标签:

添加标签

- 标题

- 作者

- 时间

- 长度

- 点击

- 评价

-

- 倾听非洲:BAABA MAAL

- 日落酒馆

- 2002-03-31 02:28

- 12582

- 1202

- 0/0

-

访谈的金山快译

访谈的金山快译

- 日落酒馆

- 2002-03-31 18:35

- 7478

- 339

- 0/0